Yesterday, Thuingaleng Muivah, the General Secretary of the NSCN-IM, returned to his birthplace — Somdal, a Tangkhul Naga village in Manipur’s Ukhrul district — after fifty years. His homecoming was marked by a renewed call for a sovereign Nagalim, a demand that has defined Naga politics for decades. His visit appeared to have official sanction. But the question that now looms is — does this revived call for sovereignty have the approval of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government?

To understand the Naga question, one must first look at its historical roots — a history deeply distinct from the rest of India’s nation-building experience.

The Historical Context

The Naga Hills were among the last territories annexed by the British in the Indian subcontinent. British presence began in 1878 with the establishment of their administrative centre at Kohima, which was then a large Angami village. The consolidation of British authority continued until 1949, when the newly independent Indian government extended its control to the Tuensang region.

Before this period, the Naga tribes existed largely independent of any central authority, whether from Assam or Burma. This historical autonomy makes their situation markedly different from places like Jammu and Kashmir, which had longstanding links with India’s cultural and political fabric.

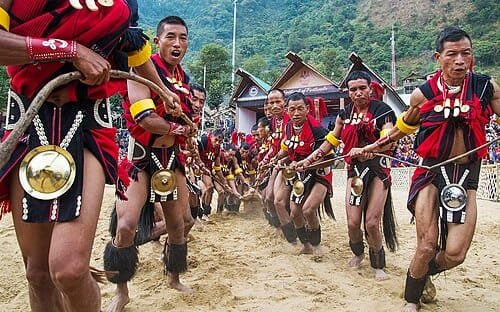

Who Are the Nagas?

Anthropologically, the Naga tribes are of Tibeto-Burman origin, ethnically and culturally distinct from the populations of the Indo-Gangetic plains and peninsular India.

Former Nagaland Chief Minister Hokishe Sema, in his book Emergence of Nagaland, explains that while neighboring groups such as the Garos, Khasis, and Mizos can be categorized within broader ethnolinguistic groups, the Nagas defy any singular classification.

“There are no composite ‘Naga’ people,” Sema writes, “but many distinct tribes speaking over thirty dialects, with each tribe forming a separate language group.”

Social structures, customs, and even physical features vary widely from tribe to tribe. The word “Naga” itself was not indigenous; it was a term given by outsiders — much like how the term “Hindu” was historically coined by Persian travelers to describe the people living beyond the Indus River.

Today, the Nagas communicate across linguistic barriers through “Nagamese”, a creole blend of Assamese, English, and Hindi — a language born of necessity rather than cultural unity. This linguistic diversity underscores the fact that a unified Naga identity is a political construction, not an ancient or natural one.

Christianity and Cultural Transformation

A major turning point in Naga society came with the spread of Christianity. The first missionary, Reverend Miles Bronson, arrived in 1836, but it was the American Baptist Reverend E.W. Clark who truly transformed the region. His baptism of nine Nagas in 1872 marked the beginning of a religious revolution.

Today, Baptist churches dominate Naga society, with over 800 churches and a majority Christian population. The missionaries played a transformative role in education and healthcare, but they also fostered a shared spiritual and political consciousness among the disparate tribes — laying the foundation for Naga unity.

The Naga Club and the Birth of Political Consciousness

The first organized expression of Naga unity came in 1918 with the formation of the Naga Club, encouraged by the British administration. Comprising village elders, officials, and educated Nagas, the Club quickly became a political platform.

When the Simon Commission visited in 1929, the Naga Club famously submitted a memorandum stating:

“We pray that we should not be thrust to the mercy of people who could never have conquered us themselves, but to leave us alone to determine for ourselves as in ancient times.”

This marked the beginning of a consistent political position — that while British rule was tolerated, integration into India was not.

World War II and the Promise of Independence

The Naga Hills gained strategic importance during World War II, particularly during the Battle of Imphal (1944) when Japanese forces under Lt. Gen. Renya Mutaguchi advanced through the region. The Nagas assisted the Allied forces with remarkable bravery.

Field Marshal William Slim, in his memoir Defeat into Victory, wrote:

“The gallant Nagas, whose loyalty never faltered… guided our columns, collected information, ambushed enemy patrols, carried supplies and brought in our wounded under fire — and often refused all payment.”

This loyalty was born of a belief that their service might earn them independence once the British departed.

The Birth of Naga Nationalism

Encouraged by British officials like Sir Charles Pawsey, the Naga Hills District Tribal Council was formed in 1945 to unite the tribes. The following year, it evolved into the Naga National Council (NNC), the first major political body representing Naga aspirations.

Initially, the NNC sought only autonomy within Assam, but by December 1946, it had shifted toward complete independence. At a public meeting in Kohima, T. Aliba Imti Ao — the NNC’s secretary — called for the unification of all Naga tribes and full freedom.

The British, about to leave India, may have quietly encouraged these sentiments to preserve their strategic influence in the frontier regions.

Insurgency and the Indian State

By 1954, the movement for Naga independence had escalated into a full-blown insurgency. The Indian Army was deployed, tasked with eliminating “terrorism.” However, the campaign soon turned brutal — marked by human rights violations, village burnings, and arbitrary killings.

While the Army eventually reasserted control, it deepened local resentment and alienation from the Indian state.

Over time, the Indian Army adapted its approach, becoming more sensitive to local realities. Yet, the political and bureaucratic leadership continued to falter. Since the formation of Nagaland in 1963, the region has endured a cycle of corruption, misgovernance, and neglect, despite receiving one of the highest per capita development expenditures in the country.

Drugs, Borders, and New Challenges

Nagaland and Manipur lie along the border with Myanmar (Burma) — a region plagued by its own insurgencies and notorious as a major center of heroin production. The trade routes passing through Imphal, Kohima, and Dimapur have turned into corridors for narcotics smuggling.

This has not only linked insurgency with the drug economy, but also triggered a public health crisis, with rising HIV cases due to needle use among addicts. The problem is now both social and security-related.

The Way Forward

India’s long-term national security interests — and the growing Chinese presence in northern Myanmar — make the stability of the Naga Hills crucial. Military and administrative presence is essential, but so are innovative political arrangements that respect Naga culture, geography, and autonomy.

While Article 371A of the Constitution provides special safeguards for Nagaland, it remains insufficient to address the deeper issues of identity, self-governance, and historical grievance.

The path ahead lies not in domination or neglect, but in dialogue, mutual respect, and genuine federalism — acknowledging that the Naga story is not one of rebellion alone, but also of a people seeking recognition, dignity, and a place within or alongside India on their own terms.