In a world obsessed with clear faces and fair skin, beauty has been confined to a narrow spectrum — smooth, unblemished, and standardized.

From cosmetic industries to digital filters, global culture keeps telling us that perfection means a spotless face and lighter tone.

But across Africa, for thousands of years, a very different philosophy of beauty has existed — one that defies this uniformity, one that celebrates the body as a living canvas of history, identity, and courage.

That philosophy is called scarification — the ancient and sacred art of carving identity and emotion into the skin.

What Is Scarification?

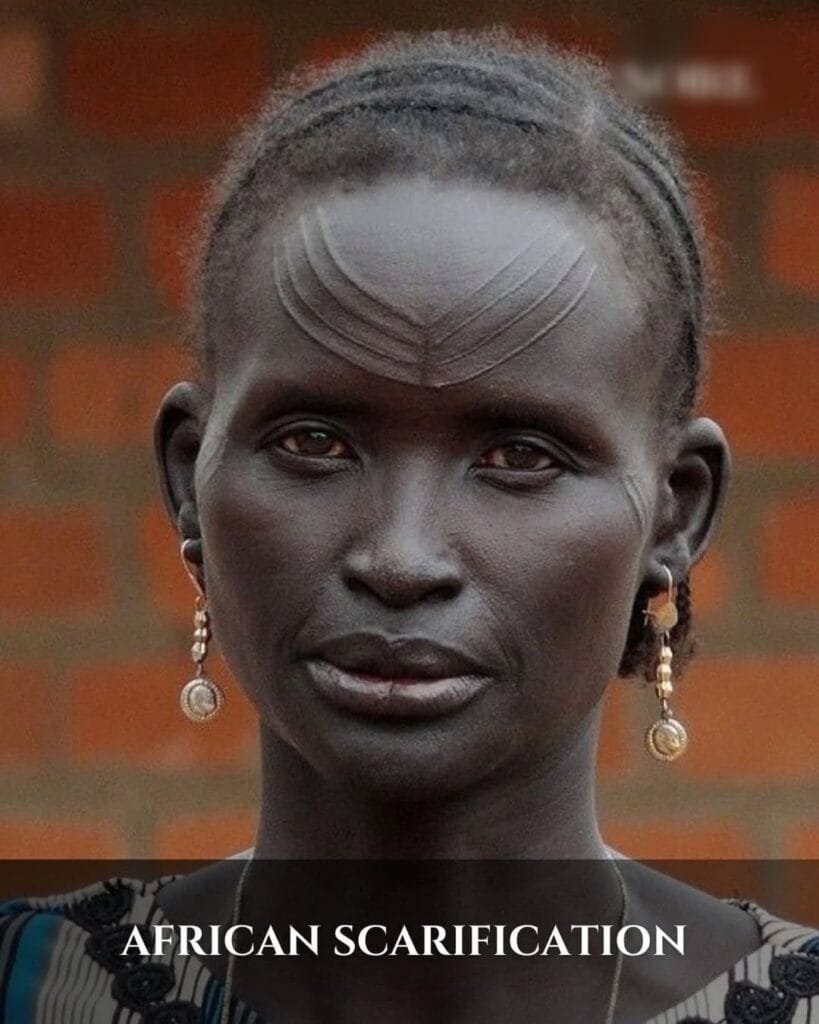

Scarification is the deliberate act of cutting, etching, or burning the skin to create permanent scars that form patterns, symbols, or designs.

Unlike tattoos, which rely on ink, scarification uses the body’s own healing process to raise the skin and form visible marks.

Each scar carries a meaning — it might represent tribal belonging, spiritual protection, bravery, beauty, or a life milestone.

In traditional African societies, the skin was not merely a surface; it was a text — a medium on which stories of lineage, love, loss, and transformation were written.

The Historical Roots: Carved in Time

Scarification is not a modern phenomenon. Archaeological and anthropological evidence traces it back thousands of years, across the breadth of the African continent — from West Africa to the Horn of Africa, from the Congo Basin to the Nile Valley.

Among the Yoruba of Nigeria, facial marks known as ila were used to denote family lineage and clan identity.

The Dinka and Nuer people of South Sudan etched parallel or V-shaped lines across the forehead as a rite of manhood and courage.

The Mursi and Surma women of Ethiopia carved their stomachs and chests as symbols of beauty and readiness for marriage.

The Makonde of Tanzania and Mozambique sculpted intricate facial designs that blended identity, spirituality, and art.

Each mark, each cut, was a declaration — “This is who I am.”

The Language of Identity

Before passports and ID cards, before borders divided the continent, the skin was the document of belonging.

Scarification served as a biological signature — a visual code that told others your tribe, lineage, social role, and ancestry.

For example:

A Yoruba child’s facial marks could reveal their hometown and even the family they descended from.

A Dinka man’s V-shaped scars showed not just his community, but also his courage in enduring the ritual without fear.

These marks were living identifiers — unique, unforgeable, and socially significant.

To belong without marks often meant being “invisible,” an outsider without a tribe or history.

Beauty in Pain: The Aesthetic Philosophy

While the modern world often links beauty to flawlessness, African aesthetics historically celebrated texture, symbolism, and endurance.

Raised scars on the face, shoulders, or torso were seen as sensual and striking.

Among many communities, women who bore intricate patterns were considered highly attractive, disciplined, and spiritually mature.

In the Mursi tribe, for example, scars on the stomach were believed to enhance a woman’s beauty and sexual appeal.

For men, scarification was a demonstration of masculine bravery and the ability to withstand pain — qualities that defined leadership and maturity.

Thus, pain was not ugliness; it was a passage.

And beauty was not given; it was earned.

The Ritual of Courage: Rite of Passage

In many African cultures, scarification was a rite of passage — the physical and spiritual journey from childhood to adulthood.

The ceremony often involved intense pain, but it was also communal, celebratory, and sacred.

Boys and girls underwent it in groups, supported by elders who sang songs of strength and ancestry.

Crying or showing fear during the process was considered shameful. Those who endured it silently emerged as true adults, ready to take responsibility, marry, or fight for their community.

In this sense, scarification was more than an aesthetic choice — it was a moral and social transformation, a visible proof of inner strength.

Spiritual and Protective Meaning

Beyond identity and aesthetics, scarification had deep spiritual and cosmological significance.

Many tribes believed that the skin connected the body to the spirit world.

Marks were therefore used as protection charms — to guard against evil spirits, sickness, or misfortune.

Some designs symbolized ancestors’ blessings, while others invoked the presence of divine power or fertility.

Among the Yoruba, certain marks were considered channels through which ase (spiritual energy) flowed.

For others, scarification was a way to maintain a tangible connection to their ancestors and deities, ensuring that identity extended beyond death.

Social Order and Recognition

Scarification also served as a social code.

It could indicate marital status, social class, or achievements in warfare.

Some tribes used special patterns for royalty or spiritual leaders, while others marked slaves differently — a practice that later took on tragic implications during the era of the transatlantic slave trade.

When enslaved Africans were taken to the Americas, their scar patterns sometimes helped them recognize each other — silent reminders of home, tribe, and lost freedom.

In this way, scarification survived as a resilient link between identity and memory, even in exile.

Colonialism and the Criminalization of Scars

The arrival of European colonial powers in Africa brought a systematic assault on indigenous traditions — and scarification was among the first to be demonized.

Missionaries labeled it “barbaric,” “pagan,” and “uncivilized.”

Colonial administrators banned it, framing it as proof of backwardness.

In the eyes of Western rulers, a “civilized” African was one who abandoned such marks and adopted European clothing and Christian values.

The body — once a sacred site of identity — was turned into a battleground of power and morality.

Even after independence, these colonial attitudes lingered.

Modern education, urbanization, and Christianity/Islam further stigmatized scarification as unhygienic or primitive.

By the late 20th century, the tradition had nearly disappeared from many regions — a casualty of globalization and modern aesthetics.

The Western Beauty Machine vs. Indigenous Pride

Today, the global beauty industry profits from promoting blemish-free perfection.

Social media filters erase scars, wrinkles, and pores — teaching millions to hate the very textures that make them human.

In this context, African scarification stands as a radical counter-narrative.

It asserts that beauty can exist in imperfection, that pain can be art, and that identity can be carved, not concealed.

Where the Western ideal says, “Hide your scars,” the African tradition answers, “Reveal them — they tell your story.”

Contemporary Revival: From Stigma to Symbol

In the 21st century, scarification is making a quiet return — not as a mass revival, but as an artistic and political reawakening.

African photographers, anthropologists, and cultural activists are documenting the last generations of scarified elders, preserving their knowledge before it vanishes.

Artists and designers reinterpret traditional patterns through modern media, exploring questions of race, memory, and decolonization.

In places like Nigeria, Ethiopia, and Kenya, a small number of young people are reclaiming scarification — not as fashion, but as a declaration of heritage and defiance.

“My scars are not wounds,” says a Nigerian artist featured in Afropunk Magazine.

“They are memories — proof that my ancestors existed on this skin before the world told me to bleach it.”

Global Misunderstandings and Appropriation

Meanwhile, in the West, scarification has been adopted in body-modification subcultures — often stripped of its cultural and spiritual meaning.

For some, it’s an aesthetic experiment or an expression of individuality.

But when detached from its African context, scarification risks becoming a spectacle rather than a statement.

True appreciation requires understanding the philosophy behind the scars — that these marks were never about decoration, but about belonging, memory, and meaning.

A Philosophical Reflection: Beauty Beyond Skin

Scarification challenges the modern obsession with flawless skin and offers a profound philosophical insight:

that the human body is not just for display — it is for storytelling.

It reminds us that pain, when embraced with purpose, can become art; that imperfection can become strength; that identity can be felt as much as it is seen.

Every raised scar becomes a text — written not in ink, but in experience.

Every mark whispers, “I have lived, I have endured, and I carry my people with me.”

The Courage to Wear History

African scarification is not about violence or vanity.

It is about courage — the courage to inscribe your story on your skin, to defy colonial shame, to remember who you are even when the world tells you to forget.

As globalization continues to bleach beauty into uniformity, these scars remind us that diversity is not a flaw — it’s the essence of being human.

The world may rush to erase scars,

but Africa turned them into art.

The world may chase whiteness,

but Africa found power in the dark and the deep.

Scarification is not dying; it’s transforming — from a bodily practice to a global statement about identity, resistance, and beauty beyond perfection.

Because in the end, true beauty is not what hides the wound — it’s what grows from it.